In the past, cholera infections were common in many countries around the globe. Now, they are mostly confined to developing regions because the disease is associated with poor nutrition, poor water quality and poor sanitation.

The proportion of people who die from reported cholera remains higher in Africa than elsewhere. In Nigeria, huge outbreaks were recorded in 1991, 2010, 2014 and 2018. In 2018, there were 43,996 cholera cases and 836 deaths: a case fatality rate of 1.90%.

Susceptibility to cholera is associated with demographic and socioeconomic factors, including age and nutritional status. Malnutrition drives transmission and severity. Vitamin B12 deficiency and gastritis are risk factors for infection.

The bacteria that cause cholera are expelled through the faeces for nearly two weeks after infection. They can be shed into the environment to infect other people.

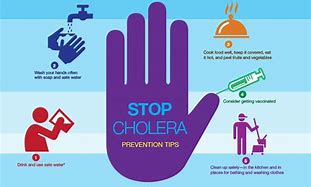

Lack of access to safe drinking water and poor personal and environmental hygiene are basic factors that promote the spread of cholera. Infection also occurs when people eat or drink something that’s already contaminated by the bacteria. Evidence from the 1995-1996 outbreak in Kano State revealed that poor hand hygiene before meals and vended water played a role.

Population congestion is also a factor in the spread of cholera. This can happen through migration to commercial hubs such as Kano. It can also happen when humanitarian disasters force displaced people to live in camps. There, they often have inadequate water supply and may be unable to observe good sanitary practices. Over 2.9 million people are currently living as internally displaced persons in north-eastern Nigeria. At least, 10,000 cholera cases and 175 related deaths were reported in Yobe, Adamawa and Borno state predominantly in crowded camps in 2018.

Living in urban and peri-urban slums promotes cholera too. This is because regular water supply and toilet facilities are not adequately available. Only 26.5% of the Nigerian population use improved drinking water sources and sanitation facilities, and 23.5% defecate in the open.

The Nigerian government has made some efforts to control the disease. It is implementing programmes to improve water supply, basic sanitation and good hygiene practices, but these are usually implemented after outbreaks. Led by the Federal Ministry of Water Resources, the government has provided 510,663 litres of water daily in 39 locations in Adamawa state, which accounted for 50% of cholera cases in 2019.

It has also provided mobile solar-powered boreholes. The International Organisation for Migration maintains 58 solar-powered boreholes in Borno state and drilled 11 new ones in 2019. It also rehabilitated 10 and connected them to solar power.

In response to an outbreak at the displaced persons’ camps in Borno state in 2017, the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency and other partners conducted oral cholera vaccination campaigns.

The oral cholera vaccine is not a part of the routine vaccination in Nigeria. It is not 100% effective against cholera and does not protect against other foodborne or waterborne diseases. It is not a longtime solution to cholera and only bridges the gap between emergency response and longtime cholera control. In 2017, reactive oral cholera vaccine campaigns were implemented in Borno to stop an outbreak. Investments in water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure are always necessary.

Health education, campaigns are conducted by outbreak investigation teams from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control following confirmation of cholera outbreaks. UNICEF has promoted chlorination of water among communities in cholera hotspots. This has benefited an estimated 4.5 million people in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states, including 680,000 displaced people in urban centres.

Much remains to be done since cholera has not been conquered completely.

Cholera has been described as a “disease of poverty” because social risk factors play significant roles in its transmission.

In line with best practices of multisectoral control, we recommend the following:

National governments in cholera-affected countries should take the lead with support from the Global Task Force on Cholera Control partners. Multi-sectoral interventions to effectively control cholera are based on a package of measures that should be well coordinated. They include creating access to safe drinking water and sanitation; improving surveillance, reporting and readiness; and community engagement to raise awareness and promote good hygiene practices.

Regular health education during and after outbreaks is necessary. Community engagement would help to identify people who would be responsible for timely reporting of suspected cases of cholera. The teams that manage outbreaks at the local, state and federal government levels should be well coordinated and respond swiftly when notified of a cholera outbreak.

These steps have been seen to work in South Sudan and Tanzania but require political will to get different sectors to collaborate.

source: HeathWise

Thousands of cases of cholera have been reported in Nigeria between January and June 2021. The northern states of Bauchi, Gombe, Kano, Plateau and Zamfara are among those affected.

Thousands of cases of cholera have been reported in Nigeria between January and June 2021. The northern states of Bauchi, Gombe, Kano, Plateau and Zamfara are among those affected.