What these great leaders have recognized, is that achieving universal health coverage (ensuring allpeople receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship) is hugely popular. Furthermore, they have realised that with genuine political commitment and increased public financing, it is possible to implement UHC reforms surprisingly quickly and benefit the entire population. This makes health reforms unusual, because they can generate national political returns quickly, as opposed to many economic and infrastructure investments that often take decades to deliver results. Rapid popular health reforms are therefore a proven vote-winner within the time frame of one presidential term. In fact, there is strong evidence to indicate that President Obama’s early health reforms were instrumental in securing his re-election in 2012.

Looking at world history, it is also noticeable how these great leaders often delivered UHC to their populations after major political transitions in their countries. This included the UK after the Second World War, Thailand after the Asian Economic Crisis in 1998 and South Africa after the end of apartheid. Many democratic governments elected in Latin America following the overthrow of corrupt dictatorships also launched UHC reforms as a quick political win. Bringing health services to everyone was one of the best ways to demonstrate that these new leaders cared about the people and that their governments represented a break with the past.

Secondly, Nigeria now has the domestic financial resources to reach UHC. In 2014, a by eminent health economists estimated that countries needed to raise a minimum of $86 per capita in public health spending in order to cover the costs of UHC. They also called on countries to allocate 5% of their GDP for this purpose. Nigeria currently only allocates 1.1% , but $86 per capita only represents 2.6% of GDP, which should be eminently affordable. Rwanda, for example, allocates 6.5% its GDP to public health spending. Furthermore it should be noted that Nigeria today is almost twice as wealthy as Thailand was in 2002, when it extended tax financed healthcare to the entire population.

One strategy Nigeria could employ to find the additional public financing for UHC would be to use savings made by reducing fuel subsidies. This is an approach being adopted by Iran and Indonesia, where leaders have recognized the importance of providing a popular social policy (free health services) to the population as they increase fuel prices. As levels of fuel subsidy spending in Nigeria have been as much as seven times the federal health budget, there would appear to be considerable scope to raise public health funding from this source.

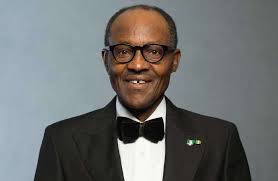

But perhaps most significantly for the likelihood of UHC success, after the recent historic elections, the Nigerian people have now voted for a progressive leader who has committed himself to bringing healthcare to the people. Following his victory, President Buhari in an open letter to the people pledged that he would: “Guarantee financial sustainability to the health sector and minimum basic health care for all.” [In other words achieve UHC]

As world history has shown, all the health and economic ingredients may be in place but it is the political catalyst that is the key to achieving UHC. Of course the President and his Government would need to plan and implement Nigeria’s own path to UHC, reflecting the country’s specific health, economic and political context. In particular, it will be vital to take into account Nigeria’s federal system to secure political buy-in at the state level and facilitate fiscal transfers to ensure that poorer regions receive their fair share of national resources. It will also be imperative that the President maintains genuine political commitment to overseeing the necessary health system reforms and that the population holds him to account on bringing effective coverage to everyone.

Source: Nigeria Healthwatch

This week’s guest blog comes from Robert Yates, an internationally recognized expert on progressive health financing. He works for Chatham House, the international affairs “Think-tank” based in London. He was one of the speakers at the Future of Health Conference held on

This week’s guest blog comes from Robert Yates, an internationally recognized expert on progressive health financing. He works for Chatham House, the international affairs “Think-tank” based in London. He was one of the speakers at the Future of Health Conference held on