“We’re very excited about the promise of this technology,” said Jacob Corn, a senior author on the study and scientific director of the Innovative Genomics Initiative at UC Berkeley. “There is still a lot of work to be done before this approach might be used in the clinic, but we’re hopeful that it will pave the way for new kinds of treatment for patients with sickle cell disease.” In tests in mice, the genetically engineered stem cells stuck around for at least four months after transplantation, an important benchmark to ensure that any potential therapy would be lasting. “This is an important advance because for the first time we show a level of correction in stem cells that should be sufficient for a clinical benefit in persons with sickle cell anemia,” said co-author Mark Walters, a pediatric hematologist and oncologist and director of UCSF Benioff Oakland’s Blood and Marrow Transplantation Programme.

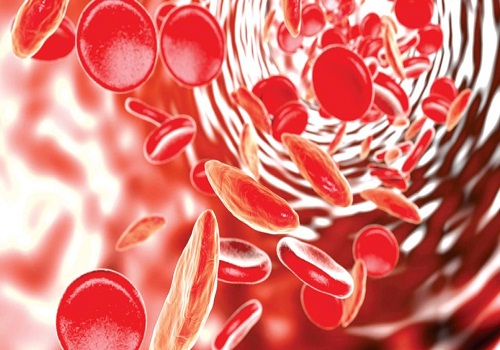

The results was reported in the journal ScienceTranslational Medicine.Sickle cell disease is a recessive genetic disorder caused by a single mutation in both copies of a gene coding for beta-globin, a protein that forms part of the oxygen-carrying molecule hemoglobin. This homozygous defect causes hemoglobin molecules to stick together, deforming red blood cells into a characteristic “sickle” shape. These misshapen cells get stuck in blood vessels, causing blockages, anemia, pain, organ failure and significantly shortened lifespan. Sickle cell disease is particularly prevalent in African Americans and the sub-Saharan African population, affecting hundreds of thousands of people worldwide.

The goal of the multi-institutional team is to develop genome engineering-based methods for correcting the disease-causing mutation in each patient’s own stem cells to ensure that new red blood cells are healthy.

The team used CRISPR-Cas9 to correct the disease-causing mutation in hematopoietic stem cells – precursor cells that mature into red blood cells – isolated from whole blood of sickle cell patients. The corrected cells produced healthy hemoglobin, which mutated cells do not make at all.

Future pre-clinical work will require additional optimization, large-scale mouse studies and rigorous safety analysis, the researchers emphasize. Corn and his lab have joined with Walters, an expert in developing curative treatments such as bone marrow transplant and gene therapy for sickle cell disease, to initiate an early-phase clinical trial to test this new treatment within the next five years.

Notably, research groups might be able to apply the approach described in this study to develop treatments for other blood diseases such as β-thalassemia, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), chronic granulomatous disease, rare disorders like Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and Fanconi anemia, and even HIV infection. “Sickle cell disease is just one of many blood disorders caused by a single mutation in the genome,” Corn said. “It’s very possible that other researchers and clinicians could use this type of gene editing to explore ways to cure a large number of diseases.” “There is a clear path for developing therapies for certain diseases,” said co-senior author Dana Carroll of the University of Utah, who co-developed one of the first genome editing techniques over a decade ago. “It’s very gratifying to see gene editing technology being brought to practical applications.”

The work is the fruit of the Innovative Genomics Initiative, a joint effort between UC Berkeley and UCSF that aims to correct DNA mutations that underlie human disease using CRISPR-Cas9, a pioneering technology co-developed by scientists at UC Berkeley that has made genome editing easier and more efficient than ever before. The project also leverages the expertise of physicians and scientists at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, a major center for research and treatment of sickle cell disease, and Carroll’s expertise in the field of genome engineering.

The research is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Li Ka Shing Foundation, the Siebel Scholars Fund, the Jordan Family Fund and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Source: MWN

A team of physicians and laboratory scientists has taken a key step toward a cure for sickle cell disease, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to fix the mutated gene responsible for the disease in stem cells from the blood of affected patients. For the first time, they have corrected the mutation in a proportion of stem cells that is high enough to produce a substantial benefit in sickle cell patients.

A team of physicians and laboratory scientists has taken a key step toward a cure for sickle cell disease, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to fix the mutated gene responsible for the disease in stem cells from the blood of affected patients. For the first time, they have corrected the mutation in a proportion of stem cells that is high enough to produce a substantial benefit in sickle cell patients.