Some of the most common causes of maternal deaths and complications include hemorrhage, prolonged obstructive labour, convulsion, infection with fever, complications arising from abortion procedures, and ruptured ectopic pregnancy according to findings from the ‘Why Are Women Dying While Giving Birth in Nigeria?’ (WAWD) Report . A Nigerian woman has a 1-in-22 lifetime risk of dying during pregnancy, childbirth, or after delivery. In most developed countries the lifetime risk is 1-in-4900.

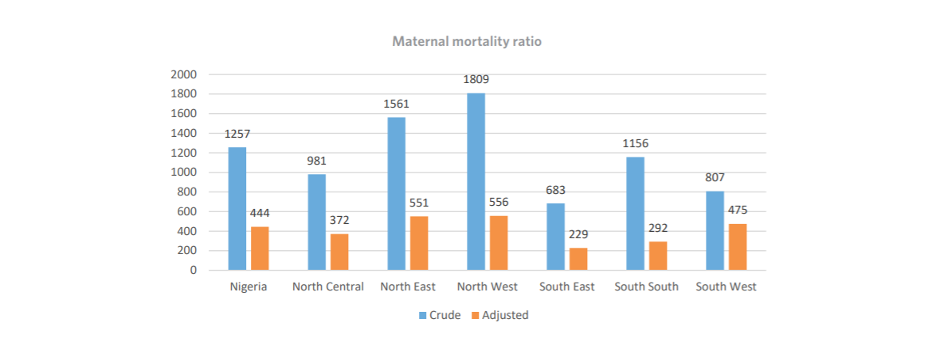

Maternal Mortality Ratio for the National and regional QED indicators on the MPD-4-QED program (1 July to 30 September 2020). Image credit: World Health Organisation

To understand the reasons behind maternal death cases, a health information system that correctly identifies and records the causes of death needs to be in place. Implementing such a system will help facilities better mitigate against preventable causes of maternal deaths, reducing its prevalence.

Globally, efforts are being made to improve the quality of maternal and perinatal care, and surveillance of maternal mortality. Nigeria is one of nine countries that is part of the WHO-led Network for Improving Quality of Care for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, known as the QoC Network. Countries in the QoC Network have agreed on a vision that every pregnant woman and newborn receives good-quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period. The vision is underpinned by the core values of quality, equity and dignity (QED). The Network was launched in 2017. One of the targets for the Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) 3 on Health and Wellbeing is to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

Following the launch, the Maternal Perinatal Database for Quality Equity and Dignity (MPD-4-QED) Programme was implemented in Nigeria in 2019 across 54 tertiary level public and private health facilities. The Programme was established to implement a standardized electronic platform for the collection and collation of maternal and perinatal data. This will enable routine healthcare data analysis and maternal and perinatal death audits and will facilitate reporting and feedback at the local, state, regional, and national levels for the improvements in clinical care performance.

Collating quality data: How the MPD-4-QED Programme is implemented

The MPD-4-QED programme collects maternal and perinatal data from at least one health facility in each state of the country, trains medical doctors (Obstetricians and Neonatologists) and medical record officers with information to empower pregnant women in caregiving decisions. With the commitment to act on quality improvement strategies, better health outcomes for mothers and newborns who use the facilities can be expected.

Medical Record Officers (MROs) are the major drivers of the MPD-4-QED programme. At each facility, MROs working in the obstetrics and gynecological department, trained to be proficient in electronic health data capture, are the data collectors.

They make rounds to the obstetric and gynecological wards, delivery rooms, operating theatres, neonatal ward, and intensive care units to conduct surveillance of medical records and complete a tablet-enabled electronic data capture form for all eligible women.

The form is completed immediately after the discharge or death of the woman and/or baby. The collected data covers the period that the woman and baby are admitted at the hospital. After collection, the MROs extract data on the care provided by midwives and doctors to the woman and her child, and their clinical care outcomes.

In the event of the death of a woman and/or baby, the clinical condition primarily responsible for the death is extracted from the medical records, as well as the contributory factors surrounding the death. Then a review is held to discuss the death, its causes, and potential ways to prevent such a death from happening again. In this way the MPD-4-QED Programme is collating quality maternal and perinatal data electronically that is helping to improve each facility’s Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (MPDSR) process.

“Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (MPDSR) is a global project,” says Dr Bosede Ezekwe of WHO Nigeria. “Including analysis of MPDSR global trends and creation of country case studies to help understand exactly why a woman and her newborn died in pregnancy, around the time of childbirth or in the postnatal period is a crucial first step towards preventing other women and newborns from dying in the same way.”

In addition to identifying the medical causes of death, Ezekwe says it is important to know the woman’s personal story and the precise circumstances of her death.

Each participating hospital has real-time access to its own electronic database through a designated code, for local audit, planning, care quality control, training, and research.

Data as a litmus test for the quality of maternal care

Between September 1, 2019 and February 10, 2021, 122,285 women and babies in 54 health facilities all over Nigeria were enrolled under the MPD-4-QED programme’s electronic platform according to a MPD-4-QED programme report. Image credit: Nigeria Health Watch

Between September 1, 2019 and February 10, 2021, 122,285 women and babies in 54 health facilities all over Nigeria were enrolled under the MPD-4-QED programme’s electronic platform according to a MPD-4-QED programme report. Image credit: Nigeria Health Watch

Having access to the Maternal and Perinatal Database (MPD) can give local, state, and federal governments an accurate picture of not just how many women are being treated at the facilities, but also how they are being treated, and where the gaps lie.

“What is happening now is people are recognizing that it’s more than just about recording deaths because it actually also reflects on the quality of care that’s provided, respectful care for women and their babies, and developing action plans to address those issues,” says Dr. Tina Lavin, Technical Officer, Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, WHO.

Lavin said promoting data and accountability is logical, and it is also about creating a culture of quality improvement. “So there has to be some desire and drive from the participating facilities that actually collected the data to act on the data,” she urged.

She added that when each state accesses its own data and looks at those areas that need attention, it might require a huge investment in terms of resources. Identifying those areas will help states tackle the challenges of maternal and perinatal deaths.

The MPD-4-QED programme is helping broaden the data available for MPDSR in health facilities. All women admitted in labour and who deliver in the participating hospitals and their newborn babies are closely monitored and their data collected. This data collection extends to all women admitted within 7 days of termination of pregnancy irrespective of the gestational age, and all babies admitted to the neonatal unit within 7 days of life regardless of where the delivery took place. Women are qualified for inclusion regardless of where they received antenatal care (ANC).

Usman DanFodio University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto, was recognised for its commitment to the MPD-4-QED programme. The hospital in a January 2021 programme report was highlighted as having one of the highest enrolments of women and babies in the country. They were also recognized for having a near-perfect maternal and perinatal death audit completion rate. In the report, two staff members, Zulkifilu Mu’azu, a senior health record officer and Muhammad Nasir Wamakko, a senior health record officer, noted that the Programme enables facilities to have data available for monitoring and decision making on how to improve quality of care in the facilities, something that had been missing for a long time.

One advantage of the platform is the way it is structured with a lot of validation rules while inputting data.

This helps in ensuring data quality and achieving accuracy in data collection. The hospital credited proper training and technical support received from the MPD-4-QED team, as well as early notifications from all wards involved in the programme for their success.

Expanding the data pool to improve quality of care in communities

Despite the 2016 adoption of MPDSR by the Nigerian government at the federal level, state-level implementation has been inadequate, because it focuses mainly on facility-based maternal deaths and sub-national MPDSR committees are unable to effectively turn the data into action.

According to the 2018 NDHS, only 39% of live births occur in health facilities, which means 61% of women in Nigeria give birth outside of health facilities. According to the WAWD report, which was a community-informed maternal death review, places of birth included faith-based centres, with Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) and at home. How are the deaths of these women who give birth in communities tracked?

The MPDSR should be extended to include community-based maternal deaths, to provide a holistic approach to MPDSR and to truly ensure greater accountability of maternal deaths. In doing so, reducing maternal mortality in Nigeria, especially when preventable.

Through community-focused MPDSR, every maternal death at home, at a faith-based centre, or with a TBA can be counted, assessed, and avoidable factors aggregated. The information generated can be used to guide the immediate implementation of solutions.

The data from community-based MPDSR can also enrich the Maternal and Perinatal Database, and provide the evidence needed to understand in real-time why women are dying while giving birth in communities and advocate governments to act at all levels to prevent the continued occurrence of these maternal deaths in communities

Source: HealthWatch

The maternal mortality rate in Nigeria is 512 deaths per 100,000 live births, and according to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), 61 percent of live births do not take place in a health facility. About 20% of global maternal deaths occur in Nigeria and more women especially those aged 15–19 die from pregnancy-related complications.

The maternal mortality rate in Nigeria is 512 deaths per 100,000 live births, and according to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), 61 percent of live births do not take place in a health facility. About 20% of global maternal deaths occur in Nigeria and more women especially those aged 15–19 die from pregnancy-related complications.